Diabetes Emergency Decision Tool

Emergency Guidance Tool

What Counts as a Diabetes Emergency?

When your blood sugar drops too low or spikes too high, it’s not just inconvenient-it’s life-threatening. Severe hypoglycemia happens when your blood glucose falls below 54 mg/dL and you can’t treat yourself. You might pass out, seize, or become unresponsive. On the flip side, severe hyperglycemia means your blood sugar climbs past 250 mg/dL with ketones in your blood or urine, signaling diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), or above 600 mg/dL with extreme dehydration, pointing to hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). These aren’t minor blips. They’re emergencies that demand immediate action.

Insulin is the most common culprit behind severe hypoglycemia. Too much insulin, missed meals, or intense exercise can send levels crashing. For hyperglycemia, it’s often missed insulin doses, illness, or new medications like SGLT2 inhibitors that trigger a dangerous rise. The CDC says about 37 million Americans have diabetes, and for those on insulin, the risk of severe hypoglycemia is as high as 30% every year. That’s not rare. It’s predictable-and preventable.

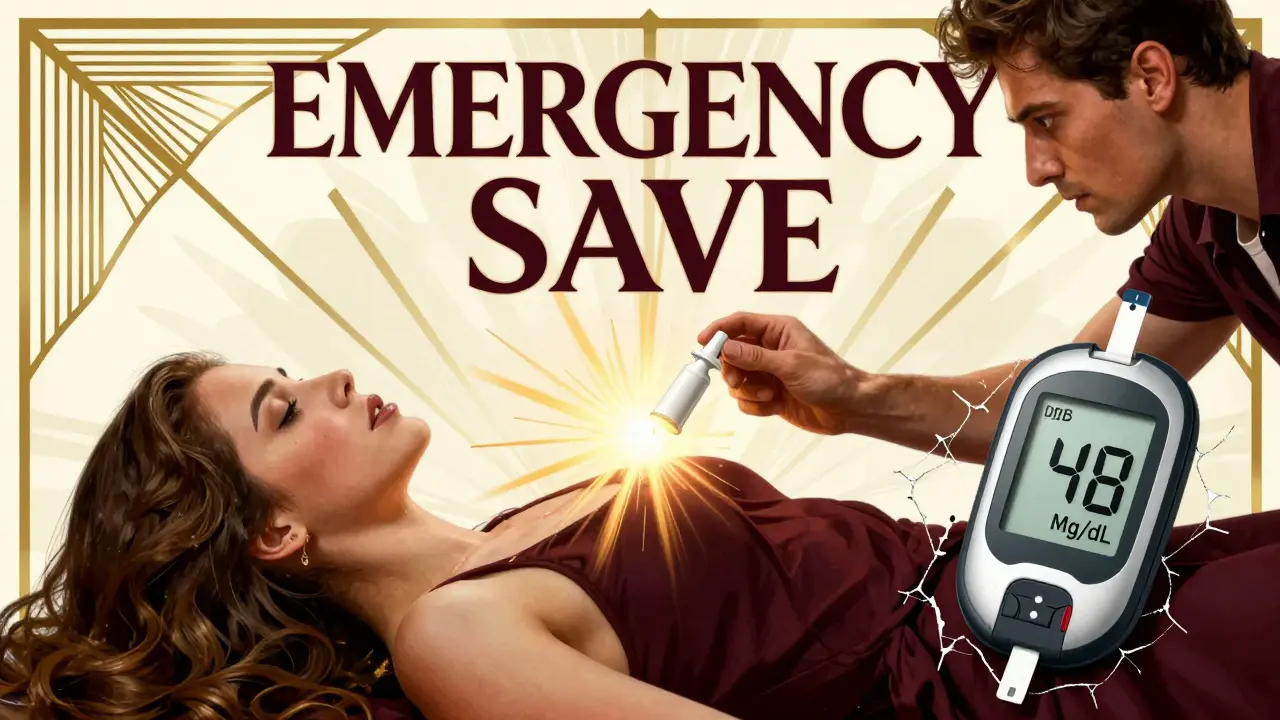

How to Treat Severe Hypoglycemia When You Can’t Help Yourself

If someone with diabetes is unconscious, confused, or seizing, don’t try to give them food or drink. You could choke them. Instead, give glucagon. It’s the only medication that can pull their blood sugar back up when they can’t swallow or respond.

There are three ways to give glucagon now-and they’re all better than the old way. The traditional glucagon kit requires mixing powder and liquid, then injecting it. Most people can’t do it under stress. That’s why new options exist:

- Baqsimi: A nasal spray. Just insert it into one nostril and press the plunger. No needles. No mixing. Takes effect in 10-15 minutes.

- Gvoke: A pre-filled autoinjector. Like an EpiPen. Press it against the thigh or arm and hold for 5 seconds.

- Traditional glucagon injection: Still works, but only 42% of caregivers can use it correctly without training.

A 2021 study found that 83% of caregivers could successfully use nasal glucagon, compared to just 42% with the old kit. Time saved? From over two minutes down to 27 seconds. That matters when every second counts.

For mild low blood sugar (between 54 and 70 mg/dL), use the Rule of 15: eat exactly 15 grams of fast-acting carbs-like 4 glucose tablets, 4 oz of regular soda, or 1 tablespoon of honey. Wait 15 minutes. Check your blood sugar again. Repeat if needed. Don’t guess. Don’t eat a whole candy bar. Too much can cause a rebound high.

How to Handle Severe Hyperglycemia: DKA and HHS

Unlike hypoglycemia, you don’t treat severe hyperglycemia at home. You call 911 or go to the ER. The body is in crisis. It’s dehydrated, acidic, and starving for energy-even though blood sugar is sky-high.

Hospital treatment follows three steps:

- Fluids: You’ll get 1-2 liters of IV saline in the first hour to rehydrate and flush out ketones.

- Electrolytes: Potassium drops dangerously low during DKA. IV potassium is added to fluids to prevent heart rhythm problems.

- Insulin: Continuous IV insulin is given at 0.1 units per kg per hour. For mild DKA (pH >7.0), some doctors now use fast-acting insulin shots, but for severe cases, IV is still required.

Never give glucagon for high blood sugar. It will make it worse. Never give insulin without checking ketones. Giving insulin to someone with HHS without fluids can crash potassium levels and cause cardiac arrest.

Key warning signs of DKA: fruity breath, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, rapid breathing, confusion. For HHS: extreme thirst, dry skin, high fever, drowsiness, vision loss. If you see these, don’t wait. Go to the hospital.

Why Most People Are Unprepared

Here’s the hard truth: 63% of people with type 1 diabetes have had a severe low that required help. But only 41% always carry glucagon. Why? Fear. Most people are terrified of using it wrong.

One mom on Reddit shared how her child’s school nurse refused to give glucagon because she’d never been trained. The child had to wait for 911. That’s not an exception-it’s the norm.

Studies show only 28% of at-risk patients get proper glucagon training. And even when they do, most never practice. Without practice, skills fade. One study found that 92% of people who practiced glucagon administration quarterly kept the skill six months later. Those who didn’t? Only 45% remembered how.

Another problem? People wait too long to seek help for high blood sugar. A survey found 58% of DKA cases happened because patients waited over 12 hours after symptoms started. They thought it was just the flu. Or they didn’t know ketones were dangerous.

What Should Be in Your Emergency Kit

Every person on insulin-type 1 or type 2-needs an emergency kit. Not just a glucagon device. Here’s what to include:

- Glucagon nasal spray (Baqsimi) or autoinjector (Gvoke)-check expiration dates every 3 months.

- Glucose tablets (4g each)-pack at least four for mild lows.

- Fast-acting carbs: small juice boxes, honey packets, or regular soda (not diet).

- Blood ketone meter and test strips-check if blood sugar is over 250 mg/dL and you feel unwell.

- Emergency contact list: your doctor, a family member, and your insulin pump or CGM manufacturer’s hotline.

- A medical ID bracelet or card stating you have diabetes and are on insulin.

Store your kit where everyone can find it-your purse, car, desk, school locker. Don’t hide it in the back of a cabinet. If you’re traveling, carry two glucagon devices. One can expire. One can get lost.

Who’s at Highest Risk-and Why

It’s not just type 1 diabetes. People with type 2 on insulin are just as likely to have severe lows. But only 34% of them carry glucagon, compared to 68% of type 1 patients. That’s a gap in care.

Black and Hispanic patients are 2.3 times more likely to be hospitalized for severe hypoglycemia than white patients. Why? Lack of access. Medicaid patients face prior authorization for glucagon 31% of the time. Private insurance? Only 12%. That’s not a medical issue-it’s a systemic one.

Older adults are also at risk. They may not recognize symptoms. Or they’re on multiple medications that interact with insulin. And they’re less likely to have someone nearby who knows how to help.

What’s New in Emergency Care

The biggest breakthrough in recent years? The beta Bionics iLet-a dual-hormone artificial pancreas that automatically gives glucagon when it predicts a low. In trials, it cut severe hypoglycemia by 72%. But it’s only available at 12 U.S. centers right now.

Next up? Dasiglucagon, a new glucagon analog that works in under two minutes. It’s in phase 3 trials and could be approved by late 2024.

Also, new apps like Eli Lilly’s Gvoke HelperApp guide you through administration with video steps. If you get a new glucagon device, download the app. Practice with it. Even if you think you know how, you might be surprised.

What to Do Right Now

If you or someone you care for uses insulin:

- Ask your doctor for a prescription for Baqsimi or Gvoke-don’t settle for the old kit.

- Practice using the device with a trainer pen. Do it once a month.

- Teach at least two people how to use it-family, friend, coworker, school nurse.

- Keep glucagon in your bag, car, and workplace. Don’t rely on one location.

- Get a ketone meter. Test if your blood sugar is over 250 mg/dL and you feel sick.

- Wear a medical ID. It saves lives when you can’t speak.

Don’t wait for a crisis. Prepare now. Because when your blood sugar crashes or soars, there’s no time to read instructions. You need to act-and you need to know how.

srishti Jain

January 1, 2026 AT 03:10Cheyenne Sims

January 1, 2026 AT 17:28Shae Chapman

January 3, 2026 AT 01:21Nadia Spira

January 4, 2026 AT 14:38henry mateo

January 5, 2026 AT 02:57Kunal Karakoti

January 6, 2026 AT 16:59Glendon Cone

January 8, 2026 AT 10:04Henry Ward

January 9, 2026 AT 15:23Aayush Khandelwal

January 11, 2026 AT 02:06Sandeep Mishra

January 12, 2026 AT 14:22Joseph Corry

January 13, 2026 AT 14:20Hayley Ash

January 14, 2026 AT 09:08kelly tracy

January 14, 2026 AT 10:27Kelly Gerrard

January 15, 2026 AT 10:45Colin L

January 16, 2026 AT 03:15